INTERNATIONAL LAW: THE INTRODUCTION OF THE FOREIGN ACCOUNT TAX COMPLIANCE ACT (FATCA) AND WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

/The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA as it is universally known, is the centerpiece of U.S. efforts to curb tax evasion everywhere. It was introduced in 2010 as the revenue-raising portion of the domestic jobs stimulus bill, the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment (HIRE) Act, but its impact is only now being felt. Since being passed into federal law, the U.S. government has negotiated various agreements with foreign nations effectively extending the enforceable application of FATCA to the global stage.

The historic legislation has made significant waves internationally, particularly in offshore financial centers where local secrecy and confidentiality laws had often made it incredibly difficult for the U.S. authorities to identify and tackle tax evasion.

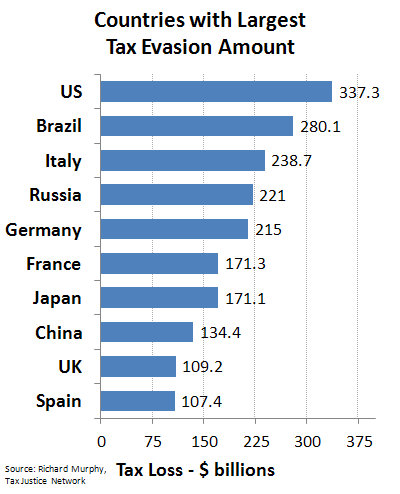

"The U.S. topped a list of countries most effected by tax evasion, with the nation projected to be losing approximately $337 billion a year."

In 2011, the Tax Justice Network estimated that tax evasion represented 5% of global GDP. The U.S. topped a list of countries most effected by tax evasion, with the nation projected to be losing approximately $337 billion a year. Given increasing global trade and growing international investment opportunities, it is a figure that was only going to spiral unless action was taken. The U.S. government's response was FATCA.

Life before FATCA

Before the introduction of FATCA, the IRS was largely reliant on the honest and accurate reporting by individuals, corporations and trustees of their foreign assets and income. International confidentiality and secrecy laws meant that the IRS could not undertake a review of foreign bank accounts and assets owned by U.S. citizens or corporations held abroad. Although the U.S. Treasury could seek the assistance of foreign courts in cases where there was clear and compelling evidence of tax evasion, it could not gain access to financial accounts on suspicion alone.

The IRS’s inability to effectively investigate tax reporting created a culture of casual tax evasion. It should be noted that unlike tax avoidance, which is the legal application of loopholes in the law to minimize tax liability (as discussed on our previous blog on Offshore Financial Centers), tax evasion is a criminal offense punishable by hefty fines and prison sentences.

"The IRS’s inability to effectively investigate tax reporting created a culture of casual tax evasion."

Shell companies would be set up offshore with a sole U.S. director and shareholder, but the income would either not be reported or would be inaccurately reported. Given that several offshore jurisdictions have legislation keeping directors' registers and shareholders' registers confidential, the IRS had no way of conducting compliance checks to see what interests U.S. citizens had in foreign companies. Foreign trusts would be established to hold assets including corporations, real estate, stock and foreign currencies, but again the assets would not be properly reported as the assets of trusts are also protected by foreign confidentiality laws. Furthermore, U.S. citizens and green card holders were living abroad, sometimes earning substantial tax-free wages, without ever declaring their foreign earned income to the IRS.

Collectively, this lax attitude towards accurate financial reporting, whether it be intentional, reckless or negligent, became alarmingly common, particularly as the movement of financial assets became easier and less expensive in an increasingly global economy. The cost to the U.S. Treasury was massive.

"Countries with Largest Tax Evasion Amount v3" by Guest2625 - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons

The Introduction of FATCA

In March 2010, FATCA became law and compelled all foreign financial institutions (FFIs) to search their records for suspected U.S. persons who held accounts with them and report their assets and identities to the U.S. Treasury. FATCA’s stated objectives include: -

- FATCA targets tax non-compliance by U.S. taxpayers with foreign accounts.

- FATCA focuses on reporting:

- By U.S. taxpayers about certain foreign financial accounts and offshore assets

- By foreign financial institutions about financial accounts held by U.S. taxpayers or foreign entities in which U.S. taxpayers hold a substantial ownership interest

- The objective of FATCA is the reporting of foreign financial assets; withholding is the cost of not reporting.

The consequences under the law for FFIs’ non-compliance are severe. If an FFI fails to enter into the necessary reporting arrangements with the IRS, a 30% withholding tax is imposed on U.S. source income and other U.S. related payments of the FFI. This is not a position any FFI wants to find itself in.

Intergovernmental Agreements

The U.S. has learned over several decades that without the appropriate international compliance and enforcement regime, federal law is of limited value. After all, FATCA has not introduced anything new in terms of taxation; U.S. citizens and residents have long been subject to reporting foreign financial interests and paying tax on their worldwide income. What FATCA sought to change was compliance with the tax code that was so regularly ignored by corporations and individuals alike.

To make FATCA effective, the U.S. used its considerable trade and political leverage to enter into intergovernmental agreements with the majority of developed foreign nations, which implemented FATCA into local law and established tax information exchange protocols. A full list of the countries that have already signed treaty agreement with the U.S. can viewed here - list of treaties.

Impact of FATCA

Despite being introduced into Federal law in 2010, most of the foreign reporting obligations did not come into force until 2013-14, following the introduction of the key filing and reporting dates contained in the intergovernmental agreements discussed above. Now that FATCA has been adopted by local law around the world, meaning enforcement of non-compliance is a much less burdensome process, FFIs have become acutely aware of their reporting obligations. The result is that the vast majority of FFIs have systematically reviewed their clients’ identities and their financial interests, ensuring they are ready to report to the IRS directly, or indirectly through their national tax authority, depending on the form of the intergovernmental treaty entered into.

"...the burden placed on FFIs has prompted several foreign financial institutions to turn away U.S. citizens or residents looking to open up a bank account."

For FFIs, the cost of opening a bank account, complying with the due diligence and reporting each year to the IRS, often makes it unprofitable to provide a banking service to U.S. citizens. So much so that the burden placed on FFIs has prompted several foreign financial institutions to turn away U.S. citizens looking to open up a bank account. Furthermore, companies are reluctant to appoint U.S. citizens as directors or officers given the heightened reporting obligations which accompany their appointment.

What can we expect going forward?

The best way to look at what the future holds is to appreciate that for the first time the IRS will be able to cross reference the tax filings and foreign bank account reporting (FBAR) of each U.S. individual and corporation, with the information reported by FFIs. The implications are massive and are expected to expose widespread tax evasion.

The reporting obligations of FFIs includes any interest in bank accounts, mutual funds, hedge funds, private equity, directors fees, pensions, annuities, real estate, beneficial interests in trust assets and much more. If U.S. persons or corporations have not fully reported any interest they will be in breach of U.S. tax code. Inaccurate reporting can now be identified with little effort. Even if U.S. individuals or corporations who have previously failed to report their foreign interests do begin to accurately report, it will not change the fact the IRS will have evidence of past negligent or fraudulent reporting. For example, if an FFI reports an individual has had an investment account in the Bahamas for the last ten years, which they have never reported to the IRS and from which they receive annual dividends, that individual will be in hot water regardless of how he reports in the current tax year.

Over the next few years you can expect to hear about the IRS pursuing those individuals or companies that have avoided paying substantial tax liability through inaccurate tax reporting, which in most cases will be treated as tax evasion. Exactly how the IRS pursues more modest sums of money that have not been properly reported remains to be seen, but there is no question the IRS will have substantial evidence to pursue thousands of individuals and corporations should it choose to.

As legal advisers, we would strongly recommend that all U.S. citizens and green card holders, wherever they reside in the world and wherever their income is generated, to seriously consider the impact of FATCA and the fundamental change in culture that is unfolding. The U.S. authorities now have the tools they has long been seeking to uncover a wide variety of tax fraud. The IRS will treat any breaches of U.S. tax code far more favorably if the individual or company comes forward, as opposed to the IRS contacting them. If you require advice on FATCA and the compliance regulations placed on FFIs, please contact the McGill Law Office. If you believe you are in breach of U.S. tax code and require advice on exploring your options we recommend you contact your accountant or a specialist tax attorney.

Content prepared by Richard Parry. © Richard Parry, 2015

....................................................

This message and the information presented here do not create or evidence an attorney-client relationship nor are they intended to convey legal advice or counsel. You should not act upon this information without seeking advice from a qualified lawyer licensed in your own state or country who actually represents you. In this regard, you may contact The McGill Law Office and then representation and advice may be given if, and only if, attorney Edmond McGill agrees to do so in a written contract signed by him.